Last Updated 1 September 2019

1/. From Arrest to Local Court

(a) Arrest and Following

Do I Have to Answer Police Questions

The general position is that you do not have to answer police questions. There are some important exceptions which are set out below. As a matter of common sense, if you are asked questions by police about a simple matter of which you are obviously innocent, it is probably a good idea to answer their questions. In other situations, speak to a lawyer first. In particular, if the police want to record an interview with you on tape or video, always say you want to speak to a lawyer first.

A police officer can request a person to provide his or her name and address if those

details are uunknown to the police officer t and if the police officer suspects on reasonable

grounds that the person may be able to assist in the investigation of an alleged

offence because the person was at or near the place where an alleged indictable offence occurred

around the time when the offence occurred: s. 11 Law Enforcement (Powers and Responsibilities) Act (hereafter LEPRA).

It is an offence to refuse to supply a name and address: s. 12 LEPRA. The penalty is

2 penalty units, or $220. It has been held that the police are entitled to demand the particulars of a suspect: DPP v Horwood [2009] NSWSC 1447.

Where a police officer reasonably suspects that a motor vehicle was or may have been

used in the commission of an indictable offence, the police officer can ask the owner,

driver or passenger of the vehicle to supply details of the driver and passengers

in the vehicle at the time of the offence: s. 14 LEPRA. It is an offence to refuse to give an answer or to give a false name or address,

carrying a penalty of $5500 or 12 months gaol: ss. 16-18 LEPRA.

Police can demand proof of identification: s. 19 LEPRA.

if police are entitled by law to require identification, they may require a person to remove a face covering for purposes of identification (s. 19A LEPRA). Failure to do so is an offence (s. 19B LEPRA).

Stop and Search.

The police have no power at common law to search someone prior to arrest: Mammone

v Chaplin (1991) 54 A Crim R 163. However under s. 21 LEPRA the police may stop and

search anyone whom they reasonably suspect has something stolen anything or otherwise

unlawfully obtained or anything used in an indictable offence.

Being sniffed by a police drug dog is not a 'search': DPP v Darby [2002] NSWSC 1157

A 'reasonable suspicion' involves less than a belief but more than a mere possibility. There must be some factual basis for the suspicion; reasonable suspicion is not arbitrary. Hearsay material can be used as the basis for a reasonable suspicion: Rondo (2001) 126 A Crim R 562 .

A police officer has the power to stop and search a motor vehicle if he/she believes on reasonable grounds that the vehicle is being or may have been used in the commission of an indictable or firearms offence, or if the police officer believes on reasonable grounds that the vehicle contains drugs or anything used or intended to be used in the commission of such an offence, or if the police officer believes on reasonable grounds that there is a serious risk to public safety and the search might lessen that risk: s. 36 LEPRA.

De Facto Arrest and Lawful Arrest

There is a distinction between de facto arrest and legal arrest. De facto arrest is where the police deprive someone of their liberty, regardless of whether this is done lawfully. Lawful arrest is where is where a person is deprived of his/her liberty lawfully. Sometimes de facto and lawful arrest happen at the same time, sometimes they happen at different times, sometimes there is never a lawful arrest.

The distinction between de facto and lawful arrest can have practical consequences in reklatin to whether or not a resist arrest charge can be proved, whether an admission made after arrest is admissible, and whether or not an action in false arrest can be established.Somtimes even courts seem to be confused about this distinction.

De Facto Arrest.

A person is arrested when police deprive him of his liberty, regardless of the words

used. A person is arrested when police make it plain to him that he is not free to

leave if he chooses: Lavery (1978) 19 SASR 515, C (1997) 93 A Crim R 81. When a person

is confronted at his home by armed police an arrest may occur unless police indicate

that the person is free to leave: Trotter (1992) 60 A Crim R 1.

Requirements of a lawful arrest

Basten JA in State of NSW v Randall [2017] NSWCA 88 (dissenting but not on this point) said that the validity of an arrest without warrant depend upon three things (at para [10]):

Physical Aspect of Arrest.

Arrest involves either submission or actual touching of the accused: Thomson [1969]

NZLR 513.

Reasonable Cause.

The arrester must have reasonable grounds to believe that the person has or is in the act of committing an offence: s. 99 LEPRA. Reasonable cause includes

hearsay: Hussein v Chong Fook Kam [1969] 3 All ER 1282. The principles relating to 'reasonable grounds to arrest' have been summarised in Hyder v The Commonwealth [2012] NSWCA 336 esp at para [15].

Purpose of Arrest.

An arrest for the purpose of investigating whether or not the person has committed

a crime, or obtaining more evidence, is an illegal arrest: Williams v The Queen (1986) 161 CLR 278, 66 ALR 385.

The purpose of the arrest must be to charge the person with an offence and bring the person before a magistrate. This remains

the case after the amendments to the Crimes Act allowing detention after arrest for

the purpose of investigation: Dungay (2001) 126 A Crim R 216. It also means that there is no power to arrest a suspect when the arresting officer has not formed an intention to charge him: NSW v Robinson [2019] HCA 46 esp at para [63], Dowse v NSW [2012] NSWCA 337 esp at para [27].

Arrest as a Last Resort

The power to arrest should only be exercised as a last resort where alternatives (such as issuing a summons or a court attendance notice) are impractical. If the power of arrest is used inappropriately for a minor offence, and the offender reacts by committing an offence such as resist arrest /assault police, evidence of these latter offences may be excluded in the exercise of the court's discretion: DPP v Carr (2002) 127 A Crim R 151. See also DPP v CAD [2003] NSWSC 196.

Notification of reason for arrest and other information

Where the police arrest a person, the police are required to inform the person that he or she is under arrest. No particular form of words is necessary as long as it is made clear to the person that he is under arrest: Inwood [1973] 2 All ER 645.

Where a police officer arrests a person, the police officer is required to inform the person of the reason for the arrest as soon as practical after the arrest: see ss. 201(1) and 202 LEPRA. See also: Code of Practice for Crime p. 11, formerly Instruction 37.14. The reason for the arrest should be made clear to the person unless:

See Christie v Leachinsky [1947] AC 573, Johnstone v NSW [2010] NSWCA 70 and State of NSW v Randall [2017] NSWCA 88 at para [32].

The arresting police are also required to provide their names and stations (ss. 201(1) and 202 LEPRAHowever, the failure to comply with this requirement does not render the exercise of the power unlawful: s. 204A LEPRA.

Search of Arrested Persons.

A person who has been arrested may be searched: s. 27 LEPRA. So may a person in lawful custody: s.28A LEPRA.

Carry Cutting.

It is an offence to have a cutting weapon when arrested: s. 547D Crimes Act. This only applies when

police locate the weapon after the defendant has been arrested: Pittman v Di Francesco

(1985) 4 NSWLR 133.

Prints and Photos.

A police officer can take particulars necessary to identify a person in custody including fingerprints, palm prints and photographs for the purpose of identification

of persons over 14: s. 133 LEPRA. Children under 14 can only be photographed or fingerprinted with a court order: s. 136 LEPRA. The purpose

is ID for the court, not the police: Carr [1972] 1 NSWLR 609. However the decision

to take fingerprints or photographs will only be impugned if not made bona fide:

McPhail and Tivey (1988) 36 A Crim R 390. In practice, anyone arrested and charged

is fingerprinted.

It has been held that s. 133 LEPRA permits the police to take photographs and fingerprints not only to establish identity but also in order to prove that the suspect had committed the crime: Regina v SA, DD, and ES [2011] NSWCCA 60.

The court can order particulars be taken of a defendant once an offence is proved: s. 134 LEPRA.

Handwriting Samples

It has been held that the predecessor to s. 133 LEPRA authorised the taking of

a sample of handwriting from a person who has been arrested to identify the person: Knight (2001) 120 A Crim R 381.

Medical Examination.

Where an officer of or above the rank of sergeant has reasonable grounds for believing

a medical examination will provide evidence, can request a doctor to examine a person

in custody: s. 138 LEPRA. This provision does not permit includes specimens

of blood and semen: Fernando

(1995) 78 A Crim R 64. However, authority to take such samples can be obtained under the Crimes (Forensic Procedures) Act (2000, discussed below.

'Custody' includes people in prison as well as people in police custody: Hawes v Governor of Goulburn Correctional Centre (NSW SC 3/9/97).

Forensic Procedures

Under the Crimes (Forensic Procedures) Act (2000) police have been given wide powers to obtain forensic samples. The provisions are extremely complex and what follows is a summary.

This legislation does not apply to DNA obtained other than by taking samples from

a suspect, such as by examining a discarded cigarette butt: Kane (2004) 144 A Crim R 496.

Forensic Procedures with the Consent of the Person

Any forensic procedure can be carried out with the informed consent of the suspect (s. 7) Children and mentally incapable people cannot give their consent (s. 8). 'Informed consent' carries with a requirement that police inform the suspect of his rights and in particular the fact that the forensic procedure may produce evidence against the suspect which could be used in court (s. 13). The giving of information to the suspect and the suspect's responses 'must if practicable' be recorded electronically (s. 15).

If the suspect is an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander, the police must notify an Aboriginal legal aid organisation, and must not ask the suspect to consent without an interview friend being present, unless the suspect expressly waives the right to have an interview friend (s. 10).

Forensic procedures can be carried out on 'volunteers' who are not suspects, with their informed consent, unless they are children or mentally incapable: s. 76.

'Non-Intimate' Forensic Procedures

Forensic procedures are divided into 'intimate' and 'non-intimate' procedures. Non-intimate forensic procedures include:

A 'senior police officer' (of the rank of sergeant or above) can order the making of a non-intimate forensic procedure on a person if the senior police officer is satisfied that:

(1) the suspect is under arrest;

(2) the suspect is not a child or an incapable person;

(3) there are reasonable grounds to believe that the suspect committed an indictable offence (or, in summary, a related offence);

(4) there are reasonable grounds for believing that the forensic procedure might produce evidence tending to confirm or disprove that the accused committed the offence; AND

(5) the carrying out of the forensic procedure without consent is justified in all the circumstances.

: s. 20 Crimes (Forensic Procedures) Act.

Intimate Forensic Procedures

Intimate forensic procedures include:

Intimate forensic procedures can only be carried by order of a magistrate or other authorised justice, after a hearing at which the suspect must normally be present: s. 22. Before making such an order, the magistrate must be satisfied of the following:

(1) that the person is a suspect (defined as s. 3 as meaning someone who has been arrested or charged with the offence, or whom the police officer reasonably suspects of having committed the offence);

(2) that there were reasonable grounds to believe that the suspect had committed a prescribed (i.e. indictable) offence or a related offence;

(3) that there were reasonable grounds to believe that the particular forensic procedure might produce evidence tending to confirm or disprove that the suspect had committed the offence of which he was suspected; AND

(4) that the carrying out of the forensic procedure was justified in all the circumstances (having regard to the gravity of the offence, the seriousness of the circumstances of the offence (?), the degree to which the suspect is said to have been involved in the offence, the age, cultural background and physical/mental health of the suspect, whether there are other practical ways of obtaining the evidence, the reasons the suspect has given for refusing, the time the suspect has been in custody, and such other matters as the magistrate considers relevant

see s. 24 and Orban v Bayliss [2004] NSWSC 428 at para [37].

The magistrate must make a finding that each of these matters have been established before an order can be made: Orban v Bayliss [2004] NSWSC 428 at para [48]. In particular, the magistrate must make a specific finding that there are reasonable grounds for believing that the suspect has committed the offence: Fawcett v Nimmo (2005) 156 A Crim R 431. It has been held that the magistrate can take into account hearsay material in making the determination: L v Lyons (2002) 56 NSWLR 600, 137 A Crim R 93. Before the magistrate makes an order requiring a suspect to give a sample of DNA, there must at least be a sample of DNA at the crime scene to match it with: Walker v Bugden (2005) 155 A Crim R 416.

Forensic Procedures and Prisoners

These provisions apply to 'serious indictable offenders', that is prisoners serving sentences for offences which carry a maximum penalty of 5 years or more: s. 3 Crimes (Forensic Procedures) Act. Police officers are given the power to make an order that a sample of hair (other than pubic hair) or a hand print, fingerprint, foot print or toe print be taken from a serious indictable offender in prison: s. 70 Crimes (Forensic Procedures) Act. A magistrate's order is required for the taking of a sample of blood or a buccal swab: s. 74.

Period of Detention

A person who is under arrest can be detained by police for the 'investigation period' (s. 114 LE (PAR) Act). This period is a 'reasonable time', but no more than 4 hours or such longer period as extended by an investigation warrant: s. 115 LE (PAR) Act.

In determining what is a 'reasonable time', certain periods can be disregarded as

'dead time.' Periods which can be treated as 'dead time' are the following (in summary):

(a) time taken to convey the person to the nearest location with facilities for conducting forensic procedures;

(b) a reasonable time waiting for the arrival of police officers or people whose special skills are necessary for the investigation;

(c) time waiting for a tape recorder or video tape to become available to record a record of interview;

(d) time to allow the accused to communicate with (presumably by phone) a friend, relative, guardian, independent person, lawyer or consular official;

(e) time taken in waiting for one of the people referred to in (d) to arrive;

(f) time taken to allow the accused to consult at the place where he is detained with one of the people referred to in (d)

(g) time taken in arranging for and allowing the accused to have medical treatment;

(h) time waiting for an interpreter to arrive or become available;

(i) time reasonably required to arrange and conduct an identification parade;

(j) time for the accused to rest, receive refreshments, or go to the toilet;

(k) time for the accused to recover from intoxication from alcohol an/or drugs;

(l) time for the police to prepare, make and dispose of an application for a detention warrant or search warrant;

(m) time reasonably required to charge the accused.

(see s. 117 LE (PAR) Act). The person must be released during the investigation period or brought before a justice, magistrate or court within the investigation period or 'as soon as practicable' after the end of that period: s. 114 LE (PAR) Act.

Extensions to the Investigation Period

A magistrate or clerk of the Local Court can authorise an extension to the investigation period for a further period, up to 8 hours (s. 118 LE (PAR) Act). The application can be made orally or in writing.

The Rights of the Suspect

The custody manager at the police station is required to caution the suspect and summarise the provisions about detention: s. 122 LE (PAR) Act. The custody manager is required to inform the suspect before any investigative procedure starts that the suspect can contact a friend, relative or lawyer to inform them of his whereabouts, consult them, or in the case of a lawyer to be present during the investigative procedures. The custody manager is required to provide facilities for the suspect to communicate with the friend, relative or lawyer (s. 123 LE (PAR) Act).

Similarly the custody manager is obliged to inform foreign nationals of their right to communicate with a consular official of the country of which the suspect is a citizen (s. 124 LE (PAR) Act).The custody manager must arrange for an interpreter to be present during any investigative procedure if it appears that because of inadequate knowledge of English the person cannot communicate with reasonable fluency in English (s. 128 LE (PAR) Act).

'Vulnerable Persons': Children, Aboriginals, people with an intellectual disability, etc

Vulnerable persons are defined as:

(Regulation 24 LE (PAR)Regulations).

'Vulnerable persons' are entitled to have a support person present during any investigative

procedure: Regulation 27 LE (PAR) Regulations. Before any investigative procedure starts, the custody manager at

the police station must inform the 'vulnerable person' that he/she is entitled to

have a support person present during any investigative procedure (reg 27).

Support Persons

If the 'vulnerable person' wishes to have a support person present, the custody manager must provide 'reasonable facilities' to enable a support person to be present (presumably access to a telephone) and allow the 'vulnerable person' to communicate privately with the support person: reg 27 LE (PAR) Regulations. This includes the right to make a phone call to a legal practitioner (reg 25 LE (PAR) Regulations).

The custody manager is to inform the support person that he/she is not restricted to acting merely as an observer in the interview, but may assist and support the person being interviewed, observe whether or not the interview is being conducted fairly, and identify communication problems with the person being interviewed: reg 30 LE (PAR) Regulations.

The caution should be repeated in front of the support person: reg 34 LE (PAR) Regulations. A copy of a summary of the suspect's rights while in custody (formerly called the part 10A document) should be given to the support person

and any interpreter for the vulnerable person: reg 30 LE (PAR) Regulations.

Breaches of these regulations may be very significant in relation to the question of whether an alleged confession of the 'vulnerable person' is admissible.

Aborigines

In addition to the rights referred to in the preceding paragraph,

the custody manager of a police station must inform an Aboriginal or Torres Strait

Islander in custody that he will inform an Aboriginal legal aid organisation that

he is the suspect is in custody for an offence, and notify the Aboriginal legal aid

organisation accordingly: reg 33 LE (PAR) Regulations This requirement does not depend on the accused making a request

for an Aboriginal legal aid organisation to be contacted. As to the effect on the

admissibility of a confession made when this regulation was not complied with, see Helmhout (2001) 125 A Crim R 257.

(b) Search and Other Warrants

Surveillance Device Material

Generally speaking recording a private conversation of parties without their consent is unlawful: s. 7 Surveillance Devices Act. One exception is where the the person recording the conversation is a party to the conversation and records the conversation in order to protect that person's lawful interests: s. 7 (3) Surveillance Devices Act. This may permit a child complainant in a sexual assault case to record a conversation with an adult accused: DW v Regina [2014] NSWCCA 28.

Surveillance Device Warrants.

The validity of a listening device warrants cannot be challenged in an inferior court

(Murphy v The Queen (1989) 167 CLR 94, Love v The Queen (1990) 169 CLR 307) but may be able to be challenged in the Supreme Court

(Carroll (1993) 70 A Crim R 162, Haynes (1996) PD [155], Ousley v The Queen (1997) 192 CLR 69, 71 ALJR 1548).

Contents of a Surveillance Device Warrant

A surveillance device warrant is required to contain (s. 20 Surveillance Devices Act):

A warrant must expressly authorise trespassing to install it for such a trespassory installation to be valid : Coco v The Queen (1994) 179 CLR 427, 68 ALJR 401.

Interception of Telephone Calls

Interception of telephone calls is governed by the Telecommunications (Interception and Access) Act (Commonwealth) 1997. What follows can only be a summary of these provisions. Generally it is not permissible to listen to or record a telephone call (the cumbersome phrase 'a communication passing over a telecommunications system' is used in the Act): s. 7 Telecommunications (Interception and Access) Act. There are some important exceptions to this general rule:

Applications for a warrant

Applications for warrants can be made by state or federal police as well as a number of agencies including the Crime Commission and the ICAC (s. 39 Telecommunications (Interception and Access) Act). Normally applications for a warrant must be made in writing, supported by an affidavit (except in urgent cases): s. 40 Telecommunications (Interception and Access) Act. Applications are made to judges or nominated members of the AAT (s. 39 Telecommunications (Interception and Access) Act). Applications are to include (s. 42 Telecommunications (Interception and Access) Act):

Matters of which a judge must be satisfied for a warrant for a class 1 offence

Class 1 offences are defined in s. 5 of the Act and include murder, kidnapping, and terrorism offences. Before issuing a warrant for a telephone intercept for a class 1 offence, the judge/AAT member must be satisfied that (s. 46 Telecommunications (Interception and Access) Act):

Matters of which a judge must be satisfied for a warrant for a class 2 offence

Serious offences are defined in s. 5D of the Telecommunications (Interception and Access) Act. For the most part, they are offences carrying a maximum sentence of more than 7 years imprisonment. Before issuing a warrant for a telephone intercept for a class 2 offence, the judge/ AAT member must be satisfied that (s. 46 Telecommunications (Interception and Access) Act):

Requirements for a warrant

Under s. 49 of the Telecommunications (Interception and Access) Act, the warrant is required to be in the prescribed form in the Telecommunications (Interception and Access) Regulations. The warrant must

Telephone Intercepts not authorised by warrant

If a telephone intercept has not been authorised by warrant, and is not authorised by one of the exceptions referred to above, it is inadmissible in evidence: s. 77 Telecommunications (Interception and Access) Act. It is important to note that this is not subject to any discretion.

Applications for Search Warrants.

A police officer can apply (normally in writing ) for a search warrant setting out

the grounds for believing that on premises there is something that is connected with

an indictable, firearms, or drug, or child pornography offence or something stolen: s. 47 LE (PAR) Act.

If the issuing justice does not record the reasons for the warrant it is invalid: Carrol v Mijovich (1992) 58 A Crim R 243, Commissioner of Police v Atkinson (1991) 54 A Crim R 378. The search warrant must record on its face the offence to which the investigation related: Carver v Clerk of Blacktown Local Court (NSW SC 13/3/1998), Dover v Ridge (1998) 5 Crim LN [905] and Mazjoub v Kepreokis [2009] NSWSC 314 esp at para [52]. A reference to superceded legislation will not invalidate the warrant as long as there is reference to an identifiable offence: State of New South Wales v Corbett [2007] HCA 32 overruling Corbett v NSW [2006] NSWCA 138.

The warrant expires after

72 hours unless extended: s. 73 LE (PAR) Act. There must be a report back

to the justice: s. 74 LE (PAR) Act .

Executing a Warrant.

An occupier's notice must be handed to an occupier over 18: s. 67 LE (PAR) Act. Anything mentioned in the warrant and anything reasonably thought to be connected with any offence may be seized: s. 49 LE (PAR) Act. Any person in the premises reasonably believed to have a thing mentioned in the warrant may be searched: s. 50 LE (PAR) Act.

Search Warrants on Drug Premises

There are specific police powers relating to 'drug premises'. Any officer of or above the rank of sergeant can apply for a search warrant for premises which he/she believes on reasonable grounds is being used for the manufacture or supply of a prohibited drug: s. 140 LE (PAR) Act. If the warrant is granted the police have the power to search the premises and any person found on the premises: s. 142 LE (PAR) Act. Generally the provisions for the execution of ordinary search warrants described above apply: s. 59 LE (PAR) Act.

Common Law Powers

Police may only enter premises without a warrant if there is:

(Lippl v Haines (1989) 18 NSWLR 620, O'Neill (2001) 122 A Crim R 510).

Notices to Produce

Police can now apply for a notice to produce addressed to a financial institution to produce records: s. 53 LE (PAR) Act.

Entrapment in State Proceedings

The situation in relation to entrapment has been changed so far as state offences in New South Wales are concerned by the Law Enforcement (Controlled Operations) Act (1997). The definition section makes it clear that a 'controlled activity' is an illegal activity (s. 3).

A law enforcement officer can make an application in writing (or, in urgent cases,

orally) to the chief executive officer of a law enforcement agency (usually the Commissioner

of Police) for an authority to conduct a controlled operation. The application must

include the plan of the proposed operation, the alleged nature of the criminal activity

or corrupt conduct being investigated, the nature of the 'controlled activity' to

be used, and a statement about whether there has been any earlier application (s. 5).

The chief executive officer may authorise the controlled operation if satisfied that

The power to issue an authority can be delegated but only

to an officer of or above the rank of superintendent (s. 29). A written statement of reasons

should be kept by the Chief Executive Officer (s. 6).

Importantly the legislation prohibits inducing or encouraging a person to commit criminal activity or corrupt conduct that the person could not reasonably be expected to engage in unless so induced or encouraged. It also prohibits conduct likely to seriously endanger the health and safety of any person, or cause serious damage to property (s. 7). In Gedeon v Commissioner of the NSW Crime Commission [2008] HCA 43 it was held that this provision was breached when the Crime Commission authorised the sale of 6 kilos of cocaine knowing it was unlikely to be recovered.

The authority must be in writing and must indicate:

A law enforcement official and a civilian authorised to

engage in a 'controlled activity' does not constitute an offence (s. 16). A certificate issued by a chief executive officer of a law

enforcement agency to the effect that he/she was satisfied of matters referred to

in the certificate is conclusive evidence that he/she was so satisfied (s. 27).

Entrapment in Commonwealth Proceedings

There are similar provisions in ss. 15G to 15J of the Commonwealth Crimes Act.

Once again, the Act does not apply of a person is intentionally induced to commit

a crime, and the person would not otherwise have committed that offence or an offence

of that kind (s. 15I)

(c) Interrogation

Children.

Police should not question a child suspected of committing an offence unless there

is a 'support person' present (not a police officer): Code of Practice for CRIME,

p. 33, replacing Instruction 37.17.

Aboriginals.

In the Northern Territory special rules have been formulated for interrogation of

Aboriginals. For example there should be a 'prisoners friend' present, the caution

should be read back by the accused, the questions should not be leading, etc. These

rules are called the Anunga Rules: Anunga (1976) 11 ALR 412. Under the Code of Practice

for Crime, the custody manager is required to ensure that Aboriginal legal aid has

been contacted: Code of Practice for CRIME, p. 12.

Police Questioning: suspects with an intellectual disability

Where a person is suspected of being developmentally delayed the interview should

take place in the presence of a guardian, relative, friend or non-police professional:

Police Instruction 37.14.

Records of Interview.

The defendant should be asked to read the interview aloud. The senior officer available

not connected with the investigation should ask the defendant if it was a voluntary

statement etc. The defendant should be supplied with a copy: Instruction 37.16.

'Preliminary Questioning' in Notebooks.

When a suspect makes a 'confession, admission or statement' in preliminary questioning,

the police officer should 'record it in full in your notebook' (Code of Practice

for CRIME pp. 25-6). 'Do not make notes elsewhere' (Police Service Handbook p. N-2).

The suspect should be asked to sign the notebook. In any subsequent ERISP, the notebook

entries should be read to the suspect who should be asked to comment on them (Code

of Practice for CRIME p. 26).

After Charge.

Once a person has been charged they should only be interviewed when necessary to

minimize loss or harm to some person, or about new matters, or to recover property:

Instruction 37.14. According to the Code of Practice for CRIME, a person in custody

has a 'right' to communicate with a friend, relative or legal guardian: CRIME at

p. 15, replacing Instruction 155.

(d) Bail

The Bail Act (2013)

The Bail Act (2013) commenced on 20 May 2014. I recommend a very good paper written by Lucinda Opper on the new act which can be found here. Subsequent to Lucinda's paper there have been some significant amendments to the Bail Act.

Applications under the Bail Act

Under the Bail Act, there can be three types of bail applications. They are (s. 48 Bail Act):

(a) a release application (made by the accused)

(b) a detention application application (made by the prosecutor)

(c) a variation application (which can be made by any 'interested person')

An 'interested person' who can make a variation application is an accused, a prosecutor, a complainant in a domestic violence offence, a person for whose benefit an apprehended violence order was made, or the Attorney-General (s. 51 Bail Act).

Offences where there is a right to release

There is a right to release on bail for offences for which the maximum penalty is a fine only, and offences under the Summary Offences Act (apart from certain specified offences): s. 21 Bail Act.

Power to grant bail in court generally

An application for bail can be made in a court where proceedings are pending in that court (s. 61 Bail Act).

An application for bail can be made in a court after conviction where an appeal against conviction or sentence has been lodged in another court but before the applicant has appeared in the other court (s. 62 Bail Act).

A court can hear an application for variation of bail decision made by that court, however constituted (s. 63 Bail Act).

Applications for bail in the Local Court

Appeals bail

Where there is an appeal from the District Court or Supreme Court to the Court of Criminal Appeal, or to the High Court, bail can only be granted if there are 'special' or 'exceptional' circumstances: s. 22 Bail Act. Under the previous Bail Act, it was held that in practice this means it is necessary to show that the appeal is most likely to succeed: Regina v Wilson (1994) 34 NSWLR 1. Where the appeal is against a sentence imposed in the District Court, it needs to be shown at least that if bail is not granted the whole sentence will be served before the matter is heard in the CCA, or that there is an overwhelming likelihood that the appeal will succeed in the CCA : Tyler (1995) 80 A Crim R 371. It is overstating the case to say that a succesful appeal must be virtually inevitable to obtain appeals bail: El-Hili and Melville v Regina [2015] NSWCCA 146 esp at para [24]. The CCA has the power to grant bail: Milsom v Regina [2014] NSWCCA 118.

It has been held that an applicant for appeals bail where there has been a Crown appeal is still required to establish special or exceptional circumstances in order to obtain bail: HT v DPP [2019] NSWCCA 141 esp at para [22].

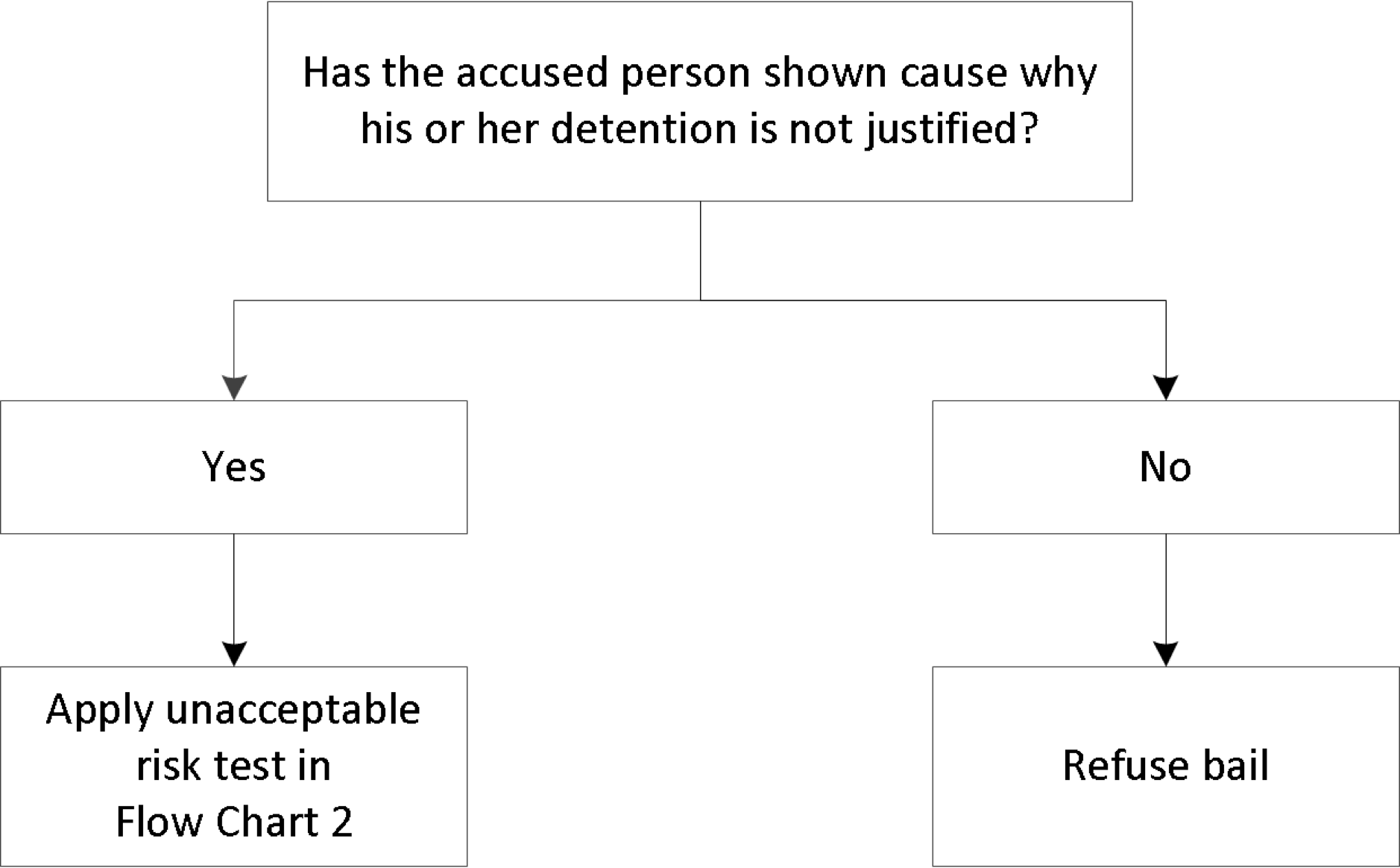

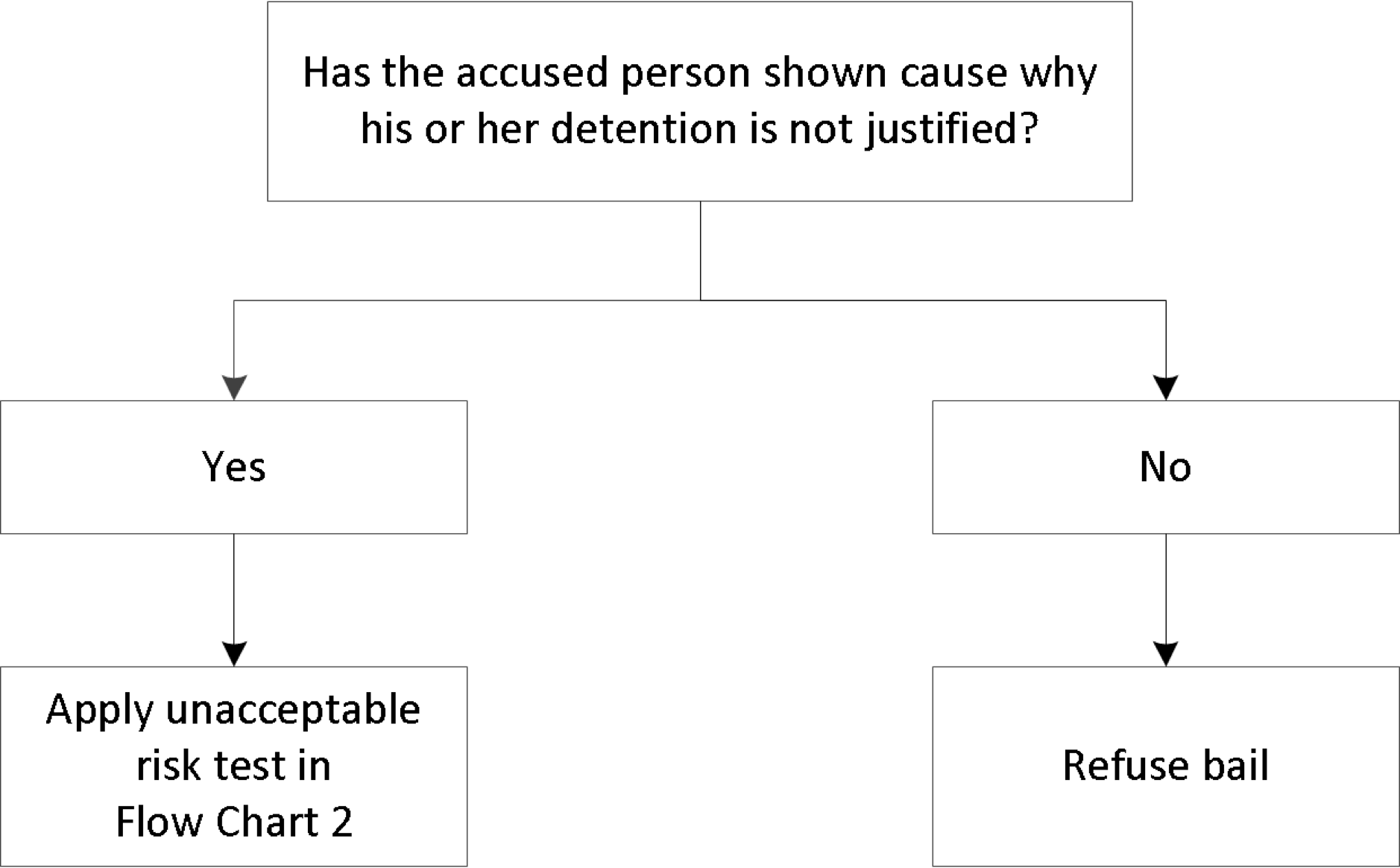

'Show Cause' Offences

Where a bail authority is considering a case of an accused who is over 18, charged with a 'show cause' offence, the bail authority must refuse bail unless the accused shows cause why his or her detention is not justified: s. 16A (1) Bail Act. Once the accused has 'shown cause', the bail authority must then make a bail decision in accordance with the 'unacceptable risk' test: s. 16A (2) Bail Act. As to the 'unacceptable risk' test see below.

'Show cause' offences are set out in s. 16B Bail Act. In summary, they include:

Procedure for 'show cause' offences

For 'show cause' offences, the applicant must demonstrate on the balance of probabilities that his or her detention is not justified, and that test is separate from the 'unacceptable risk' test: DPP v Tikomaimaleya [2015] NSWCA 83 esp at para [25]. However, in many cases the considerations for each test may be the same: DPP v Tikomaimaleya [2015] NSWCA 83 esp at para [24].

It is not necessary to show special or exceptional circumstances in order to show cause: Moukhallaletti v DPP [2016] NSWCCA 314 esp at para [55]. A single powerful factor, or a powerful combination of factors may show cause: Moukhallaletti v DPP [2016] NSWCCA 314 at para [54].

In Regina v Gountounas [2018] NSWCCA 40 there were mixed views about whether significant delay in bringing a matter to trial could satisfy the 'show cause' requirement. Fullerton J said that significant delay in bringing a matter to trial was not of itself sufficient to show cause (para [40]), and in view of the strength of the Crown case had little weight (at para [44]). Simpson J said that the delay in bringing the matter to trial had significant weight (at para [2]). McCallum J said that the significant delay could be enough to show cause (at para [55]).

Flow Chart of decisions for 'show cause' offences

Section 16 Bail Act contains a flow chart of decisions for 'show cause offences' under the Bail Act:

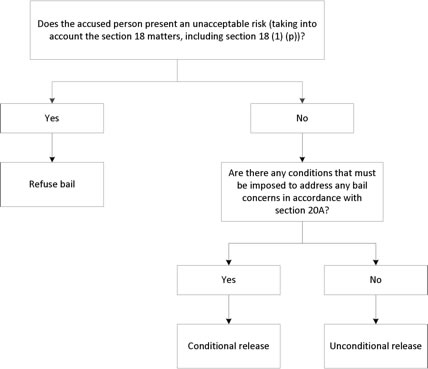

Flow chart of decisions under the Bail Act

Section 16 Bail Act contains a flow chart of decisions under the Bail Act:

Is there an 'unacceptable risk'?

For other offences, the first issue which arises a 'bail authority' (an authorised police officer, or justice, or judge) determining bail is assess any 'bail concerns' of the defendant:

In determining assessing any 'bail concerns', the court is to consider the following matters, and only the following matters (s. 18 Bail Act):

(3) A bail authority is to consider the following matters, and only the following matters, in deciding whether there is an unacceptable risk:

(a) the accused person’s background, including criminal history, circumstances and community ties,

(b) the nature and seriousness of the offence,

(c) the strength of the prosecution case,

(d) whether the accused person has a history of violence,

(e) whether the accused person has previously committed a serious offence while on bail,

(f) whether the accused person has a history of compliance or non-compliance with bail acknowledgments, bail conditions, apprehended violence orders, parole orders or good behaviour bonds,

(g) whether the accused person has any criminal associations,

(h) the length of time the accused person is likely to spend in custody if bail is refused,

(i) the likelihood of a custodial sentence being imposed if the accused person is convicted of the offence,

(j) if the accused person has been convicted of the offence and proceedings on an appeal against conviction or sentence are pending before a court, whether the appeal has a reasonably arguable prospect of success,

(k) any special vulnerability or needs the accused person has including because of youth, being an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander, or having a cognitive or mental health impairment,

(l) the need for the accused person to be free to prepare for his or her appearance in court or to obtain legal advice,

(m) the need for the accused person to be free for any other lawful reason,

(n) the conduct of the accused person towards any victim of the offence, or any family member of a victim, after the offence,

(o) in the case of a serious offence, the views of any victim of the offence or any family member of a victim (if available to the bail authority), to the extent relevant to a concern that the accused person could, if released from custody, endanger the safety of victims, individuals or the community,

(p) the bail conditions that could reasonably be imposed to address any bail concerns in accordance with section 20A.(q) whether the accused person has any associations with a terrorist organisation (within the meaning of Division 102 of Part 5.3 of the Commonwealth Criminal Code),

(r) whether the accused person has made statements or carried out activities advocating support for terrorist acts or violent extremism,

(s) whether the accused person has any associations or affiliation with any persons or groups advocating support for terrorist acts or violent extremism.

It has been stressed that the length of time the accused is likely to spend in custody is a significant matter: Regina v Alexandris [2014] NSWSC 662 esp at para [12].

The views of the police about whether or not bail should be granted are irrelevant: DPP v Mawad [2015] NSWCCA 227 esp at para [35].

In determining whether or not the offence is to be regarded as a serious offence, the following matters are to be considered (s. 17(4)):

(a) whether the offence is of a sexual or violent nature or involves the possession or use of an offensive weapon or instrument within the meaning of the Crimes Act 1900,

(b) the likely effect of the offence on any victim and on the community generally,

(c) the number of offences likely to be committed or for which the person has been granted bail or released on parole.

Some very recent cases have said that the onus is on the prosecution to establish that there is an unacceptable risk if the accused is granted bail: Regina v Alexandris [2014] NSWSC 662 esp at para [10]). Cases in other jurisdictions with a similar test to the 'unacceptable risk' test have stated that although the risk must be more than a tenuous one or the worst fear, it is not necessary for the prosecution to establish that the risk is more probable than not: see for example Haidy v DPP [2004] VSC 247 esp at paras [15] to [16]. Some cases have emphasised that assessing 'unacceptable risk' involves not simply determining whether or not there is a risk that (for example) the offender will re-offend, but balancing that risk against the consequences for the accused (including the accused's right to be at liberty) if bail is refused': see for example Woods v DPP [2014] VSC 1 esp at para [47].

Where there is no unacceptable risk, the bail authority must either release the defendant without bail, dispense with bail, or grant unconditional bail (s. 18 Bail Act).

Second Issue: Where there is are 'unacceptable risk', can it be sufficiently mitigated by bail conditions?

Where the bail authority has determined that there is an 'unacceptable risk', the bail authority must then determine whether or not the unacceptable risk can be sufficiently mitigated by bail conditions. Again, it has been held that the onus is on the prosecution, on the balance of probabilities, to establish that the 'unacceptable risk' cannot be mitigated: Regina v Lago [2014] NSWSC 662 esp at para [10].

If the 'unacceptable risk' cannot be mitigated by bail conditions, bail can be refused: s. 19 Bail Act.

Third Issue: What should the bail conditions be?

Bail conditions can only be imposed to mitigate an unacceptable risk. Bail conditions can only be imposed if (s. 20A (2) Bail Act);

(a) the bail condition is reasonably necessary to address a bail concern, and

(b) the bail condition is reasonable and proportionate to the offence for which bail is granted, and

(c) the bail condition is appropriate to the bail concern in relation to which it is imposed, and

(d) the bail condition is no more onerous than necessary to address the bail concern in relation to which it is imposed, and

(e) it is reasonably practicable for the accused person to comply with the bail condition, and

(f) there are reasonable grounds to believe that the condition is likely to be complied with by the accused person.

Bail conditions can be:

Conduct Requirement

A conduct requirement is a requirement that a person do or refrain from doing anything, but not providing security: s. 25 Bail Act.

Security requirement

A security requirement is a requirement that the accused or one or more other persons agree to forfeit a specified amount of money if the accused fails to appear in court, with or without security: s. 26 Bail Act.

A security requirement is only to be imposed to mitigate the risk of the accused not appearing in court (s. 26 (5)), and only if conduct requirements could not mitigate thata risk (s. 26(6)).

Character acknowledgment

A character acknowledgment is an acknowledgment that a person is acquainted with the accused and regards him as a responsible person who is likely to comply with bail: s. 27 Bail Act.

Accomodation requirement

A court may impose an accomodation requirement on a child to the effect that bail will not be granted until the authorities have made suitable arrangements for the accomodation of the child: s. 28 Bail Act.

Pre-release requirements

A bail condition is a pre-release requirement if the condition must be complied with before the person is released on bail. The only bail conditions which may be pre-release requirements are (s. 29 Bail Act):

Enforcement conditions

A court may impose an enforcement condition, requiring the defendant to comply with specified kinds of police directions to monitor compliance: s. 30 Bail Act.

Limitations on jurisdiction to consider bail

The Local Court and the District Court can make a decision about appeals bail after conviction if the accused has not yet appeared in a higher court: s. 62 Bail Act.

The Local Court can consider bail after committing an accused for sentence or trial to a higher court, but not after the accused has appeared in the District Court or Supreme Court: s. 68 Bail Act.

Further applications for bail

Where a court has refused bail, it is not to hear a further release application or a detention application unless (s. 74 Bail Act):

However, this does not apply to an application to the District Court after an application has already been made to the Local Court: Barr (A Pseudonym) v DPP [2018] NSWCA 47 esp at paras [55] to [63].

Proof in bail applications

The purposes of the Bail Act include a requirement that bail authorities determining a bail application have regard to the presumption of innocence and the general right to be at liberty: s. 3 Bail Act. This suggests that the onus of proof is on the prosecution.

The burden of proof is on the balance of probabilities: s. 32 Bail Act.

The rules of evidence do not apply in bail applications: s. 31 Bail Act.

Crown Appeals

If the Crown appeals against a decision to grant bail and immediately so informs the court, the decision is stayed for 3 business days or until the Supreme Court decides otherwise (s. 40 Bail Act). There is no 'principle of restraint' in relation to applications for detention made in the CCA after Supreme Court bail has been granted: Regina v Marcus [2016] NSWCCA 237, esp at para [27].

Applications for bail to the Supreme Court

As from 3 June 2019, applications for bail must be filed with submissions and all documentation in support of the bail application including affidavits, documents confirming the consent of the person with whom the applicant wishes to reside, reports, and character references. There is a practice note about filing Supreme Court bail applications, Practice Note SC CL 11. There is a Supreme Court bail application form.

(e) Crime Commission and Related Bodies

The NSW Crime Commission

The NSW Crime Commission is increasingly important in the criminal investigatory process. What follows is simply some suggestions about the basics of appearing in the Crime Commission.

Appearing for an Witness in the Crime Commission

A person giving evidence before the Crime Commission can be legally represented (s. 22 Crime Commission Act). A particular legal representative can be refused leave to appear if the Commissioner believes on reasonable grounds and in good faith that such representation will prejudice its representation (s. 22 Crime Commission Act).

The Crime Commission can and usually does as a matter of course direct that evidence

before it, and even the fact that a witness has given evidence before it, not be

'published': s. 45 Crime Commission Act.

Evidence Before the Commission

The rules of evidence do not apply in proceedings (s. 23 Crime Commissions Act), so objections are often reduced to complaints about ambiguous questions. In particular, objections based on the privilege against self-incrimination do not apply: s. 39 Crime Commission Act. Legal professional privilege does apply: s. 39(4) Crime Commission Act. So does the privilege attached to religious confessions: s. 40 Crime Commission Act.

By far the most important thing to know about proceedings in the Crime Commission

is that evidence given by a witness is not admissible in proceedings against that

witness (except for proceedings for perjury and related offences) if the witness

objects: s. 39 Crime Commission Act.

The Commissioner can declare that all answers or all answers of a particular class

will be regarded as being given under objection: s. 39(6). If there is the faintest

suspicion that your client is a suspect, you should advise him/her to object to giving

evidence.

Failing to attend when served with a summons, or failing to take the oath, or failing

to answer questions, is an offence which carries 20 penalty units or 2 years gaol: s. 25 Crime Commission Act.

The requirements of proof of a failure to take an oath or affirmation have been strictly

construed in Fehon v Domican (2002) 127 A Crim R 592 .

Providing the prosecution with transcripts of an accused's evidence from the Crime Commission

In X7 v Australian Crime Commission [2013] HCA 29 a majority of the High Court held that there was no power to compulsorily examine an accused about an offence with which he has been charged (per French CJ and Crennan J at para [54], Hayne and Bell JJ at para [156], Kiefel J at para [162]).

The High Court has held that where the evidence of an accused who has given evidence before the Crime Commission about an alleged offence has been supplied to the investigating police and the prosecution, any resulting trial will give rise to a miscarriage of justice: Lee v the Queen [2014] HCA 20.

The Crime Commission Act has been amended to permit the Crime Commission to seek leave of the Supreme Court to compulsorily examine an accused person about an offence: s. 35A Crime Commission Act. Whether or not this provision overrules X7 v Australian Crime Commission [2013] HCA 29 is not clear. At least before a person is charged, the prosecution is entitled to have access to the transcript of the accused's evidence at ICAC: McDonald and Maitland v Regina [2016] NSWCCA 306.

(f) Local Court Proceedings

What Offences are Summary Offences?

Summary offences are offences which:

Summary Proceedings: Commencing Proceedings

An information for a purely summary offence must be laid within 6 months of the offence

being committed: s. 179 Criminal Procedure Act. Importantly, the 6 month time limit does not apply to indictable matters being dealt with summarily. However, if the matter is a penalty notice matter and the defendant has elected to have the matter dealt with in the Local Court, the time limit is extended to 12 months: s. 37A Fines Act.

The

power to ignore defects in the information under s. 16 Criminal Procedure Act does

not include a change to the elements of the offence: Ex parte Lovell; re Buckley (1938) 38 SR NSW 153, Ex parte Burnett; Re Wicks [1968] 2 NSWLR 119. The information

must contain all the essential elements of the offence: John L v Attorney General of New South Wales (1987) 163 CLR 508 esp at para [14],

Stanton v Abernathy (1990) 19 NSWLR 656.

Query if a charge can be withdrawn by an informant without being withdrawn dismissed:

Gregg v O'Connor (Sully J, 21/4/92), overruled in Lay v Cleary [Bulletin 67]. A magistrate

has no power to recharge: Suters v Harrington [CN 113].

A magistrate can order a stay of proceedings: DPP v Shirvanian (1998) 44 NSWLR 129.

Summary Proceedings: Service of a Brief

In all summary proceedings, except those for which a penalty notice may be issued, if the defendant pleads not guilty the prosecution must serve on the defendant a copy of the brief of evidence, including all witness statements and proposed documentary exhibits, 14 days before the hearing or such other time as the magistrate determines (s. 183 Criminal Procedure Act). It appears that the brief should include listening device warrants and telephone intercept warrants (DPP v Webb [2000] NSWSC 859) but not search warrants (DPP v Southorn [1999] NSWSC 786).

If the brief is not served, the magistrate may dispense with service, adjourn the

proceedings (s. 187 Criminal Procedure Act),

or refuse to admit the evidence (s. 188 Criminal Procedure Act). In determining whether or not to refuse to admit the evidence the magistrate is exercising a discretionary judgement and should weigh up the competing policy considerations including the quick and efficient disposal of criminal proceedings (on the one hand) and the public's interest in prosecuting offenders: DPP v Fungavaka [2010] NSWSC 917.

The Prosecution Duty of Disclosure in the Local Court

The prosecution in Local Court criminal proceedings has the same obligations of disclosure as the Crown in higher court criminal proceedings. That includes disclosure of any document which may allow the defence to pursue a 'proper an fruitful course in cross-examination', including matters going to credit, such as prior convictions of prosecution witnesses: Bradley v Senior Constable Chilby [2020] NSWSC 145.

Must the defendant be present?

It has been held that where a defendant is not on bail, it is not necessary for the defendant to be personally present during a hearing if he or she is legally represented: McKellar v DPP [2014] NSWSC 459.

Adjournments of Summary Proceedings

Refusal of an adjournment to a defendant can result in a procedural unfairness: Noble v DPP (2000) 118 A Crim R 305.

Where a defendant has been refused legal aid there is a right of appeal to the Legal Aid Review Committee (s. 56 Legal Aid Commission Act).

Where a defendant has appealed to the legal Aid Review Committee, or intends to so appeal, the court must adjourn the proceedings if the appeal is bona fide and not vexatious or frivolous or intended to delay proceedings unless there are special circumstances: s. 57 Legal Aid Commission Act.

In Lewis v Spencer [2007] 179 A Crim R 48 Rothman J said (at para [11]):

Prima facie the existence of an appeal or an intention requires the adjournment. It is only in circumstances where the appeal or intention to appeal is not bona fide, not frivolous or vexatious or not otherwise intended “to improperly hinder or improperly delay” the conduct of the proceedings that the adjournment may not be granted.

Summary Proceedings: Open, Closed, and Non-Publication Orders

Generally, summary proceedings are to be in open court, that is open to the public and the media: s. 191 Criminal Procedure Act. This general rule is subject to some important statutory and common law exceptions. In particular, under the Court (Suppresion and Non-Publication Orders) Act (2010) courts can make suppression or non-publication orders as to the identity of the accused, a witness, or any party to proceedings, or as to the evidence in proceedings, for a limited period.

In sexual assault cases (in particular in this context including indecent assault), the court can close the court (s. 291 Criminal Procedure Act). Such an order can include suppression of the name of the accused: Crampton v DPP (NSW C of A, 7/7/1997). In a decision about the predecessor of this section, it was held that the interests of the accused were relevant in determining whether or not to make an order forbidding publication: Nationwide News v District Court of NSW (1996) 40 NSWLR 486. Those interests include the effect that publicity might have on the accused's mental health or that of his family: AB (a pseudonym) v Regina (No. 3) [2019] NSWCCA 46 esp at para [59].

At common law, the power to make a non-publication order was limited. The name of an accused can be suppressed if it is necessary to secure the proper administration of justice: C v R (1993) 67 A Crim R 562 at 565. It was held that the District Court had no power to order the non-publication of the fact of a verdict even if there were to be later trials of the same accused: John Fairfax Publications v District Court of New South Wales (2004) 61 NSWLR 344.

Order of Addresses

An argument that the defence has the right to address last in summary proceedings has been rejected: Mason v Lyon [2005] NSWSC 804.

The magistrate's decision

The magistrate is required to give reasons for his or her decision including sentence: Roylance v DPP [2018] NSWSC 933 esp at para [14].

Summary Proceedings: Costs

Normally costs will not be awarded to a successful defendant unless the investigation

was unreasonable or the proceedings were initiated without reasonable cause: s. 214 Criminal Procedure Act.

An adjournment can be granted on condition that the Crown pays costs: Le Bouriscot

(1996) PD [178].

Indictable Proceedings Dealt with Summarily.

Indictable proceedings may dealt with summarily if they a Table 1 or Table 2 offence. The election cannot be made after the evidence commences or the facts are tendered (s. 263 Criminal Procedure Act). Where an election is made the maximum penalty is generally 2 years imprisonment (s. 267 Criminal Procedure Act, for Table 1 and s. 268 Criminal Procedure Act, for Table 2).

A magistrate cannot impose a cumulative sentence on a prisoner who is serving a sentence which would mean that the new sentence would expire more than five years after the existing sentenced commenced : s. 58 Crimes (Sentencing Procedure) Act.

Table 1

Table 1 offences are to be dealt with summarily unless the prosecutor or the defendant

elects (section 260 Criminal Procedure Act).

They are generally more serious than Table 2 offences. The complete list of Table

1 offences can be found in Schedule 1 of the Criminal Procedure Act. The offences include:

Table 2

Table 2 offences are to be dealt with summarily unless the prosecutor elects (s. 260 Criminal Procedure Act). They are generally the less serious offences. The complete list of Table 2 offences can be found in Schedule 1 of the Criminal Procedure Act. The offences include:

(g) Committals

Committals were until 2018 an administrative proceeding in the Local

Court to determine whether or not a person charged with an indictable offence should

be committed for trial or sentence in the Supreme Court or District Court. As from 30 April 2018, committals are simply proceedings for committing a person charged with an indictable offence for trial or sentence (s. 3 Criminal Procedure Act). Effectively, these changes pass the responsibility for determining whether or not there is sufficient evidence for an accused to stand trial, from an independent judicial officer, to a salaried prosecutor.

Procedure in Committals: 'Charge Certificates'

The magistrate hearing the committal must set a timetable for the prosecution to serve a copy of the brief (including statements of all witnesses and any other material ressonably capable of being relevant to the strength of the prosecution case or the defence case) on the defendant (s. 61 - 62 Criminal Procedure Act). There is a continuing obligation on the prosecutor to serve material evidence on the defendant (s. 63).

The Dirctor of Public Prosecutions (through a solicitor) is required to prepare a 'charge certificate' stating the charges to be proceeded with, any backup or related charges, and certifying that there is sufficient evidence to establish each charge (s. 66 Criminal Procedure Act). The charge certificate must be filed in court and served on the accused on a date set by the magistrate usually no more than 6 months after the first return date of the court attendance notice (s. 67 ). If the charge certificate is not filed in time, the magistrate has the power to discharge the defendant (s. 68 ).

Procedure in Committals: Case Conferences

After the Charge Certificate is filed, in cases where the defendant is legally represented, and pleads not guilty to at least one offence, there is required to be a 'case conference' (s. 70 Criminal Procedure Act). The purpose of the case conference is to determine whether or not there are any charges to which the defendant is prepared to plead guilty, and to identify the issues in the trial including the agreed or disputed facts (s.70 Criminal Procedure Act).

The case conference is between the prosecutor and the defendant's lawyer. The initial case conference must be in person or by audiovisual link. Subsequent case conferences may be held by telephone (s. 71 Criminal Procedure Act). The defendat's legal representative is required to obtain instructions from the defendant and explain the benefits of a plea of guilty: s. 72 Criminal Procedure Act. Where there are multiple accused, there must be a seperate case conference for each accused unless the prosecutor and all the accused consent (s. 73 Criminal Procedure Act).

Case Conference Certificate

After the case conference, the prosecutor is required to prepare and file a Case Conference Certificate: s. 74 Criminal Procedure Act. The matters which must be included in the certificate are set out in s. 75 Criminal Procedure Act, but include the offers made by the prosecution and the defence, whether any of these offers have been accepted, which charges the prosecution intends to proceed with, and whether or not the prosecution will seek to make a submission that the discount for the plea be reduced or should not apply. There must be a certificate signed by the accused's lawyer to the effect that the lawyer has explained to the defendant the benefits of a plea of guilty (s. 75 (2) Criminal Procedure Act).

Where the prosecution does not file the case conference certificate in time, the magistrate can adjourn the proceedings, or can discharge the accused (s. 76 Criminal Procedure Act).

Where the accused makes a plea offer after the case conference certificate is filed, thatoffer can be filed separately: s. 77 Criminal Procedure Act).

The case conference certificate and any discussions in the case conference are generally not admissible in other proceedings except sentence proceedings: s. 78 Criminal Procedure Act.

Directing witnesses to give evidence in committals

The power of directing witnesses to attend and give evidence during the committal proceedings has been retained even though magistrates no longer have the power to discharge defendants at committal: s. 82 Criminal Procedure Act. If one of the parties to the proceedings applies for a witness to give evidence at committal, and the other party consents, the magistrate must give the direction: s. 82(4). The purpose of retaining the power to direct witnesses to give evidence is so as to better understand the case against the defendant and facilitate charge negotiations.

If a witness is not required to give oral evidence, the witness' statement can be tendered. Practitioners should be very conscious of the fact that if a crucial witness is not required for cross-examination, and the witness's statement is tendered at the committal, if that witness later dies or is so ill that he/she cannot give evidence, the statement can be tendered at trial: s. 285 Criminal Procedure Act. As a result in if a witness gives damaging evidence against the accused, which evidence is in dispute, it may be advisable to require that witness to give evidence at committal. Even if nothing is achieved in cross-examination, the simple fact of the witness having to give an account on oath creates a potential prior inconsistent statement.

Witnesses who cannot be required to give evidence

Complainants in cases of sexual assault, sexual servitude, child prostitution, or the production of child abuse material where the complainant was under the age of 16 years cannot be directed to attend and give evidence ib committal proceedings: s. 83 Criminal Procedure Act.

Witnesses who cannot be required to give evidence only if there are 'special reasons ... in the interests of justice'

The magistrate should not require a witness in an offence involving violence (eg attempted murder, reckless wounding, reckless inflict grievous bodily harm, abduction, robbery, sexual assault) to give evidence unless there are 'special reasons ... in the interests of justice': s. 84 Criminal Procedure Act. The phrase 'in the interests of justice' has been held in another context to refer to incorporate 'as a paramount consideration that an accused person should have a fair trial' : Chapman v Gentle (1986) A Crim R 29.

'Special reasons'

Special reasons may include where the Crown case is weak, ID in issue, inconsistent versions, victim's willingness to testify: Baines v Gould (1993) 67 A Crim R 297. Special reasons may include where the complainant in a sexual assault case is vague about the dates of the offences: Kennedy (1997) 94 A Crim R 341, TS v George (1998) 5 Crim LN [843]. This applies to indictable matters which can be dealt with summarily unless summary jurisdiction is actually offered: Kant (1994) PD [261], CN [152].

Substantial Reasons

For other types of offences, the magistrate should not require a witness to give evidence unless there are 'substantial' reasons in the interests of justice: s. 82 Criminal Procedure Act.

The following case law relates to previous versions of this provisions. 'Substantial reasons' is 'obviously much wider' than special reasons: Kennedy (1997) 94 A Crim R 341. 'Substantial' does not mean special. It is not necessary to show that the case is exceptional or unusual. It may be that substantial reasons could be shown in a majority of cases: Losurdo v DPP (1998) 44 NSWLR 618, (1997) 101 A Crim R 196 (approved by the Court of Appeal in Losurdo (1998) 44 NSWLR 618, 103 A Crim R 189), this decision appears to have the specific approval of the former Attorney General: see 'Committals in NSW' (2000) 74 ALJ 24).

It is necessary to show that the reasons 'have substance in the context of the nature of committal proceedings and the provisions of the Justices Act relating to them': Losurdo (1998) 103 A Crim R 189.

'Substantial reasons' can include a case where cross-examination might substantially undermine the credit of a significant prosecution witness: Losurdo v DPP (1998) 44 NSWLR 618. They can also include a case where the matters to be the subject of cross-examination go only to the exercise of the discretion of the trial judge (and thus strictly outside the jurisdiction of the magistrate): Losurdo v DPP (1998) 44 NSWLR 618. The availability of 'Basha' type voir dires and pre-trial applications at trial is no justification for not permitting cross-examination at the committal: Dawson v DPP [1999] NSWSC 1147. The magistrate needs to consider separately in relation to each witness whether the witness should be required: Hanna v Kearney (1998) 5 Crim LN [867]. 'Substantial reasons' might include narrowing the matters in dispute: Hanna v Kearney.

In JW v DPP [1999] NSWSC 1244 Simpson J said:

It is not possible to define the boundaries of "substantial reasons" in this context: Losurdo, C of A, pp 622, 632. A potential narrowing of the issues to be determined at trial, if the defendant is committed, is within the term; so also is the possibility of establishing the foundation for a challenge to the admission or admissibility of evidence (Hanna p 8; Losurdo, C of A pp 631-2); the possibility of significantly undermining the credibility of a Crown witness (Losurdo, C of A p 631); clarification of the evidence proposed to be called so as to avoid a defendant being taken by surprise at a trial (Losurdo, C of A, p 631); and the opportunity of gaining relatively precise knowledge of the case against the defendant (Hanna, p 5).

In Sim v Magistrate Corbett [2006] NSWSC 665 Whealy J. said (at para [20]) of these applications:

20 I shall now set out, in summary form, my understanding of a number of the relevant principles. Because of its brief nature, this statement will not be as elegantly expressed as the full statement of the principles in earlier decisions. Secondly, I will not attempt to summarise every principle arising from previous authority. Thirdly, I will emphasise, where necessary, matters that are of significance to the present dispute. I take the relevant principles to be as follows: -

A witness cannot be required for cross-examination if the Crown indicates that the Crown no longer relies on the evidence: DPP v Tanswell (1998) 103 A Crim R 205. Where a witness has been required for cross-examination because of particulars matters, normally cross-examination will be restricted to those matters.

Committals: Taking of Evidence

If a witness is directed to give evidence, that evidence is to be given orally (including the evidence in chief) unless the parties consent or there are substantial reasons in the interests of justice why the evidence should not be given by tendering the statement (ss. 85 and 86 Criminal Procedure Act).

Evidence at a committal must be taken in the presence of the defendant unless the defendant is excused or if the defendant is not present for any good or proper reason: s. 87 Criminal Procedure Act.

Committals: Open, Closed, and Non-Publication Orders

Generally, committal proceedings are to be in open court, that is open to the public and the media: s. 57 Criminal Procedure Act.

This general rule is subject to some important statutory and common law exceptions. In particular, under the Court (Suppresion and Non-Publication Orders) Act (2010) courts can make suppression or non-publication orders as to the identity of the accused, a witness, or any party to proceedings, or as to the evidence in proceedings, for a limited period. In sexual assault cases (in particular in this context indecent assault), the court can close the court (s. 291 Criminal Procedure Act) and can also forbid the publication of part or all of the evidence (s. 292 Criminal Procedure Act). Such an order can include suppression of the name of the accused: Crampton v DPP (NSW C of A, 7/7/1997). In a decision about the predecessor of this section, it was held that the interests of the accused were relevant in determining whether or not to make an order forbidding publication: Nationwide News v District Court of NSW (1996) 40 NSWLR 486.

At common law, the power to make non-publication orders is more limited. The name of an accused can be suppressed if it is necessary to secure the proper administration of justice: C v R (1993) 67 A Crim R 562 at 565.

Committals: Costs

Costs can be awarded if the defendantis discharged or if the defendant is committed for trial or sentence on a different charge to that contained in the Court Attendance Notice: s. 116 Criminal Procedure Act. The application for costs must be made on the day when the charge is dismissed or : Fosse

(1989) 42 A Crim R 289. Costs will only be awarded if the proceedings were initiated

without reasonable cause or bad faith or the investigation was unreasonable or improper: s. 117 Criminal Procedure Act. There is no power to award costs in commitals under the Costs in Criminal Cases Act: DPP v Howard (2005) 64 NSWLR 139.

Effect of a No Bill

A no bill will only justify a stay of later proceedings if there is a degree of double

jeopardy (such as a case being no billed during the course of the trial): Mellifont

(1992) 64 A Crim R 75, Swingler (1995) 80 A Crim R 471. See also Regina v Burrell [2004] NSWCCA 185. In particular if there is a no bill after discharge at committal, the Crown will not be prevented from filing a further ex officio indictment: D v Regina [2016] NSWCCA 60 (not currently available on the internet).

Counsel's Brief.

Police who search an advocate's papers may be in contempt of court even if they believe

that it contains documents suspected of being stolen: MacDonald and Shilling (1993)

70 A Crim R 478.

Local Court Flow Chart

Following a reader's suggestion, I have prepared a Local Court flow chart.

2/. Trial Procedure and Appeals

(a) Subpoenas.

Legitimate Forensic Purpose.

Counsel calling upon the subpoena should be able to identify with precision the legitimate

forensic purpose for which the document is sought: Saleam (1989) 39 A Crim R 406, Alister v The Queen (1983-4) 154 CLR 404. It

must be 'on the cards' that the documents would assist the defence case. A report

by a principal Crown witness about the case is an example of such a document, even

if nothing is known about its contents: Alister at 414, 451. Prima facie

anything which might provide for proper and fruitful cross-examination is allowable:

Maddison v Goldrick [1976] 1 NSWLR 651 esp at 663-4, Saleam. For example, in a case where the prosecution relied on only a small proportion of a large group of a large group of intercepted calls, there was held to be a legitimate forensic purpose in requiring production of the other tapes: Regina v Taylor (2007) 169 A Crim R 543.

It is not a 'legitimate forensic purpose' to want to check if the Law Enforcement (Controlled Operations) Act has been complied with: AG v Chidgey [2008] NSWCCA 65.

Width.

A subpoena will be set aside if it is too wide, for example if it requires production

of all documents relating to a particular subject area (Small (1938) 38 SR (NSW)

564) although the words 'relating to' in themselves are not necessarily fatal: Spencer

Motors v LNC [1982] 2 NSWLR 921. Once the documents are produced it is too late to

take this objection: Saleam.

Public Interest Immunity.

When public interest immunity is claimed, the court must weigh up the public interest

in non-disclosure with the public interest in the administration of justice. In a

criminal case it is sufficient if the accused can establish that the documents will

materially assist his case: Alister.

Special Classes of Public Interest Immunity.

Some classes of evidence will not be required to be disclosed unless the evidence

is necessary to establish the innocence of the accused:

Costs.

It seems that costs cannot be ordered in favour of a party who successfully opposes production of

documents under subpoena: Stanizzo v Complaint [2013] NSWCCA 295 and Ansett

Holdings (Qld SC, (1997) 94 A Crim R 7) but compare Carter v Mallesons (WA FC 15/7/93).

(b) Trial Procedure

Adjournments.

Normally an unrepresented accused should be granted an adjournment if he can prove

that it was through no fault of his own: Dietrich v The Queen (1993) 177 CLR 292, 67 ALJR 1 (1992) 64 A Crim R 176, Small (1994) 72 A Crim R 462. Lack of an adequate interpreter may

suffice to quash a conviction: Saraya (1994) 70 A Crim R 515. Where the Crown seeks

an adjournment, the court can tell the Crown that the adjournment will not be granted

unless the Crown agrees to pay costs: Moseley (1992) 65 A Crim R 452.

Constitutional Guarantee of Jury Trial.

Under s. 80 of the Constitution a person

tried on indictment for a Commonweath matter is guaranteed jury trial even if he

consents to summary trial: Brown v The Queen (1986) 160 CLR 171, 60 ALJR 257. Verdicts must be unanimous: Cheatle v The Queen (1993) 177 CLR 541, 67 ALJR 76 esp at para [73]. This does not mean that there must be 12 jurors: Brownlee v The Queen (2001) 207 CLR 278, 75 ALJR 1180.

Judge Alone Trial.

A person can elect to be tried by judge alone if the DPP consents: s. 132 Criminal Procedure Act. The judge alone election must be made no later than 28 days before the trial, except by leave of the court: s. 132A Criminal Procedure Act. The

election is made by the accused signing a Judge Alone Election under s. 132 Criminal Procedure Act. If the DPP does not consent to the judge alone procedure, the judge may still order a judge alone trial if the accused consents and it is in the interests of justice to do so: s. 132 (4) Criminal Procedure Act. The provision states that the court may refuse the application if the crial will involve the application of community standards, such as reasonableness, negligence, indecency, obscenity, or dangerousness (s. 132 (5) Criminal Procedure Act). A judge can also order a judge alone trial if there is a substantial risk of jury tampering: s. 132(7) Criminal Procedure Act.

Where the accused seeks a judge alone trial, and the prosecution opposes it, there is no presumption in favour of a judge alone trial, nor does the accused have a burden of proof to establish that there should be a judge alone trial, although there is an evidentiary onus: Regina v Belghar [2012] NSWCCA 86 at para [96]. The fact that the accused elects to be tried by judge alone is a relevant factor in determining whether or not a judge alone trial would be in the interests of justice: Regina v Simmons and Moore (No. 4) [2015] NSWSC 259, approved in Redman v Regina [2015] NSWCCA 110 at para [13]. There is no consensus in the cases that where there are issues of credibility that factor militates strongly in favour of a jury trial: Regina v Simmons and Moore (No. 4) [2015] NSWSC 259 at para [75], approved by the NSW Court of Criminal Appeal in Redman v Regina [2015] NSWCCA 110 at para [14]. In Redman the Court of Criminal Appeal held that it was an error of law to reject an application for a judge alone trial on the basis of an assumption that a jury was a superior tribunal of fact in a word against word case (at para [17]).

There cannot be a judge alone trial in a prosecution under a Commonwealth law, because of s. 80 of the Constitution: Brown v The Queen (1986) 160 CLR 171, Alqudsi v The Queen [2016] HCA 24 esp at para [115].

The accused can withdraw his consent to a judge alone trial at any time before trial

by signing and filing an Election under s. 132A (3) Criminal Procedure Act. It appears that an accused cannot withdraw his election to be tried judge alone after the trial has commenced: Regina v Hevesi-Nagy [2009] NSWSC 755.

The judgment justifying a verdict in a judge alone trial must refer to the relevant principles of law including warnings of which a jury would be directed to take into account: s. 133 Criminal Procedure Act, Fleming v The Queen (1999) 197 CLR 250, 73 ALJR 1.

Stay of Proceedings

A permanent stay of proceedings will only be granted in an extreme case: Jago

v District Court (NSW) (1989) 168 CLR 23 at 34.